Jacob: 1806 - 1871

Harriet: 1808 - 1888

Martin: 1837 - 1896

Aura: 1839 - 1940

George: 1864 - 1941

Jacob Fouts was born in 1806 to Henry Fouts who emigrated from Baltimore, Maryland, to Jefferson County in 1820. Henry was a farmer but his son had aspirations of becoming a builder. To that end he went to Philadelphia and worked in an apprenticeship where he learned mechanical engineering and architectural design. In 1827, after completing his apprenticeship, he came to Cleveland as a master builder. He had a long career as an architect and builder and erected many buildings in the Cleveland area. In the 1837 Ohio City Directory he is shown as a “carpenter” living on Church Street. While studying for his life’s work in Philadelphia Jacob met and married Harriet Cleckner. Together they gave birth to several children including Martin who came into this world on April 4, 1837.

Martin attended high school in Cleveland and at the age of 18 entered Bryant, Stratton and Folsom’s Commercial College. His first permanent employment was as a clerk in the freight office of the Cleveland & Mahoning Railroad Company in 1858. He was soon made cashier of the local freight office but in 1861 took on the job as a passenger conductor for that railroad giving him an opportunity to see, first hand, the railroad passenger experience. He kept at this for about one year when an opportunity arose.

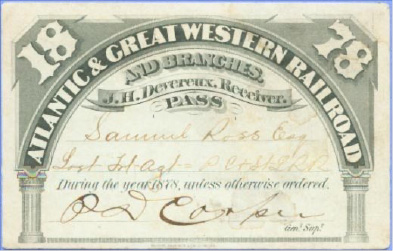

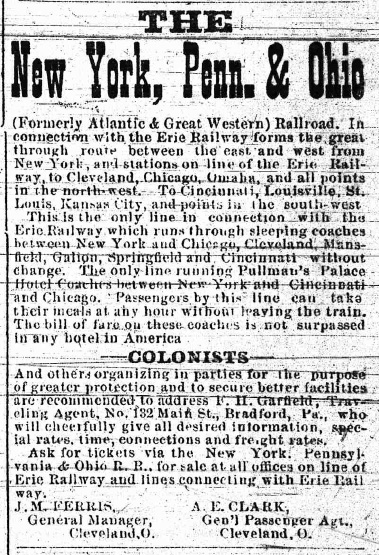

In 1862 he was made joint depot and ticket agent of the Atlantic & Great Western, the Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati & Indianapolis, and Lakeshore Railroads, the office then being located on Scranton Avenue at the junction of all the tracks. In that position, with the addition of the ticket agency of the New York, Pennsylvania & Ohio Railroad, Martin remained for 28 years. In October of 1890 he was promoted to the general agency of the passenger department in which capacity he worked until his untimely and sudden death in 1896 at the age of 59 years. As a general agent he was responsible for the manipulation of passenger traffic as well as seeking new business for the companies that employed him. Martin was a member of the City Passenger Agents’ Association, and, for many years, was treasurer of the Mahoning Mutual Benefit Association.

At the time of Harriet Fouts’ death and when Martin passed away also, they were living at 275 Franklin Street, a small but interesting Second Empire style home with a generous porch that wrapped across the front and down the west side of the house. This house, whose address today is 4206 Franklin Blvd., remains.

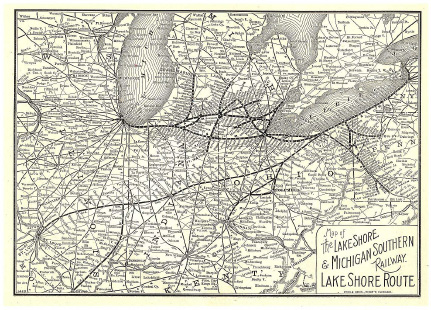

On June 17, 1862, Martin married Aura Lathrop, the daughter of Sandford Lathrop, a merchant, who came from Vermont and settled in Ashtabula County in 1820, later moving to Cleveland in 1848. Martin and Aura had only one child, a son, George E. Fouts, who was born February 28, 1864. George graduated at the Cleveland High School at age eighteen, spent two years in Adelbert College, expecting to choose some profession, but reconsidered his decision and followed in the footsteps of his father. He became a clerk in the Erie ticket office in 1884, and remained so until October 1890, when he succeeded his father as joint agent of the “Big Four,” Lakeshore & Michigan Southern and New York, Pennsylvania & Ohio railroads, having charge of both offices, Cleveland and Erie. September 14, 1893, George was married to Mary Agnes Lutye of Cleveland, six years her husband’s junior.

George eventually moved to Wilmette, Illinois, taking his mother with him. Aura Fouts died in Wilmette in June of 1940 at the ripe old age of 101 years. George followed her in death the next year, October, 1941, at the age of 77 years. Jacob, Harriet, Martin, Aura and George are all buried at the Monroe Street Cemetery.

The following excerpt was taken from the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History with the article being written by H. Roger Grant from the University of Akron:

While water traffic on both Lake Erie and the Ohio and Erie Canal did much to develop Cleveland, it took the appearance of the railroad to make the community's industrial takeoff a reality. From the 1860s to the 1960s, railroads served as the principal transporter of goods and people to and from the Forest City. Not long after the steam locomotive made its 1829 American debut, Clevelanders realized the potential for this novel transportation form.

The economic dislocations triggered by the Panic of 1837 initially prevented backers of the proposed Cleveland, Columbus & Cincinnati railroad, chartered in 1836, from turning their plans into reality. Eventually, though, a stronger economy led to line surveys, acquisition of rights-of-way, and actual construction of a railroad in the late 1840s. Cleveland's railroad era officially began on November 3, 1849 when the CC&C's lone engine was coupled onto a string of flatcars near River Street. The Cleveland Herald commented, "The whistle of the locomotive will be as familiar to the ears of the Clevelander as the sound of church bells." The CC&C opened its first segment, 36 mi. to Wellington, in July 1850 and completed the remaining line into Columbus the following February. Its first Cleveland depot stood on the lakefront near W. 9th Street. That same month, the Cleveland & Pittsburgh, which traced its corporate origins back to the 1836 charter of the Cleveland, Warren & Pittsburgh, dispatched trains over its new 26-mi. line between Cleveland and Hudson. By 1853 that carrier had entered Pittsburgh. Also, a 62-mile branch, initially organized in 1851 as the Cleveland, Mt. Vernon & Delaware Railroad, opened in 1852 between Hudson and Millersburg via Akron.

Railroad building in the Cleveland area continued at a brisk pace, but most of the early lines were under-capitalized and subject to the economic panics which occurred regularly during the 19th century. Falling into receivership, the lines often were consolidated, reorganized, and expanded after receiving new capital. This process eventually created the major rail lines that operated in the Cleveland area during the 20th century. In the early 1850s the developing network of independent roads from New York to Chicago touched Cleveland in the early 1850s. Using the 1848 charter of the Cleveland, Painesville & Ashtabula, Cleveland promoters laid tracks between the Forest City and the Ohio-Pennsylvania state line, reaching their destination in 1852. The next year the Cleveland & Toledo, an amalgamation of several "paper" companies that dated back to the mid-1840s, received permission to link these two Ohio communities, and soon the firm reached the west bank of the Cuyahoga River. In 1869 these separate companies, together with the Michigan Southern & Northern Indiana and the Buffalo & Erie, became the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railway Co. Dominated by New York interests, the LS&MS provided single management control of passenger and freight operations between Buffalo and Chicago. The Cleveland & Mahoning Valley Railroad also was included in Cleveland's first wave of steam railroad construction. Although chartered in 1848, sufficient backing was not forthcoming until Western Reserve promoters, led by Jacob Perkins, pledged their own fortunes to the scheme, and this future component of the Erie railroad took shape. By 1857 rails linked Cleveland with Warren and Youngstown. The C&MV not only gave Cleveland another railroad, it also opened up the rich Mahoning Valley coal fields to local industries and to the Great Lakes export trade.

The devastating impact of the Panic of 1857, coupled with the outbreak of the Civil War 4 years later, virtually halted railroad building in northeast Ohio. Even with peace in 1865 and a relatively healthy economy, railroad construction in the Cleveland area languished except for the 101-mile Lake Shore & Tuscarawas Valley Railway. This predominantly coal-hauling line opened on August 18, 1873, between Lorain and Uhrichsville. The LS&TV faced subsequent reorganizations and expansions until after the turn of the century, when it became the Cleveland, Lorain & Wheeling Railway and later, part of the Baltimore & Ohio system. The end of the Civil War also saw the opening of a new Union Depot on the city's lakefront near W. 9th St. Although the Panic of 1873 produced exceedingly difficult times for railroad expansion, an upturn in the economy after 1878 sparked a second wave of railroad building in both northeastern Ohio and the nation. Included in this second wave was the Valley Railroad begun on the eve of the Panic of 1873 by several Cleveland businessmen, including Jeptha H. Wade and Nathan P. Payne. This company had to wait out the depression but finally completed its Cleveland-to-Canton main line, via Akron; service commenced in 1880. Although the Valley Railroad transported quantities of coal as the result of its extension south of Canton, hard times brought on by the Panic of 1893 plunged it into receivership. Reorganization in late 1895 as the Cleveland Terminal & Valley Railroad brought new vitality. Like the Cleveland, Lorain and & Wheeling, the CT&V entered the orbit of the B&O.

Another second-wave road was the narrow gauge Cleveland, Canton & Southern, also a coal-hauler. An outgrowth of the Ohio & Toledo and the Youngstown & Connotton Valley railroad companies, this line reached Cleveland from Canton and Kent in Jan. 1882, under the flag of the Connotton Northern Railroad. Like the others, it was susceptible to economic downswings, and the recession of 1884-85 threw the Connotton Northern into a receivership that produced the Cleveland & Canton Railroad, a standard gauge carrier. The Panic of 1893 prompted further corporate reshaping when the Cleveland & Canton became the Cleveland, Canton & Southern. Ultimately, in 1899 the property, which gave Cleveland convenient access to east Ohio coal fields, found a financially healthy home within the Wheeling & Lake Erie system.

By far the most significant development of the second-wave period for Cleveland was the creation in 1881 of the New York, Chicago & St. Louis Railway, better known as the Nickel Plate Road. Spearheaded by the Nickel Plate's promoters, a combination of easterners and Ohioans, built a nearly 600-mi. road in less than 600 days. By 1882 the company connected Buffalo, NY, with Chicago, via Cleveland; in fact, the road's officials selected Cleveland as its headquarters. Entry into the city from both the east and west involved the purchase of 2 independent short lines, the Cleveland, Painesville & Ashtabula (Cleveland to Collamer) and the Rocky River Railroad (Cleveland to Rocky River). Within a week after the Nickel Plate's official opening, its owners sold out to the Vanderbilts, a business family that controlled numerous railroads, including the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern. The Vanderbilts protected their position in the LS&MS at the expense of the Nickel Plate, which languished until the New York Central Railroad, successor to the Vanderbilt empire, sold it on the eve of World War I. The sale of the Nickel Plate was the preeminent example of how control of many local roads rapidly gravitated toward New York or other eastern corporate centers during the 19th century.

Builders of the Nickel Plate Road had the good sense to recognize that by the 1880s the country's railroad enterprise was headed in a new direction. Companies would be more than short lines such as the Lake Shore & Tuscarawas Valley or the Valley Railroad that wandered into the hinterlands; they would link large urban centers. This desire for regional "system building" led to the formation by 1900 of several powerful roads in Cleveland. The New York Central controlled 3 firms: the LS&MS, the Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago & St. Louis Railway (the "Big 4," including the former Cleveland, Columbus & Cincinnati), and the Nickel Plate Road; the B&O operated the Cleveland, Lorain & Wheeling and the Cleveland Terminal and Valley roads; the Pennsylvania Railroad dominated the Cleveland & Pittsburgh; and the Erie acquired what originally had been the Cleveland & Mahoning. Only the Wheeling & Lake Erie lacked the status of being a major regional concern. As noted above, ultimate control of all these roads was held outside of Cleveland.

Union Depot

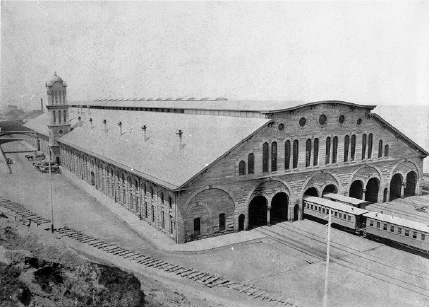

UNION DEPOT was the name given to the 2 major railroad stations erected in Cleveland before 1930. Prior to the construction of the first Union Depot in 1853, the railroads serving the city each maintained its own small depot. The first union depot, built at a cost of $75,000, consisted of a group of wooden sheds centrally located at the foot of the hill where Bank (W. 6th) and Water (W. 9th) streets met the lakeshore. After it burned in 1864, the second Union Depot was opened near the same site in 1866. At the time of its construction, the new depot, measuring 603'x180', was the largest building under 1 roof in the country. Built at a cost of $475,000, its walls were made of Berea sandstone and it was among the first buildings to utilize structural iron. A 96' tower dominated the station's southern facade when it was dedicated on November 10, 1866.