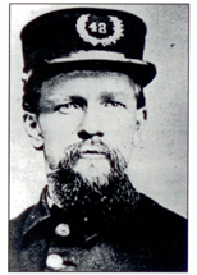

John Michael Kick 1840 - 1875

A good citizen, a brave soldier, and a faithful officer

The morning of May 9, 1875, was not unlike most Sunday mornings for L.A. Benton who owned a jewelry store at 230 Superior Street. Mr. Benton arrived at his store around 9:00 AM to wind the watches he had for sale since damage is caused to them by allowing them to run down. He entered his store and proceeded to the rear where he unlocked his safe. No sooner had he opened the safe than a man wearing a black mask showed himself and demanded that Benton should surrender and step aside. Benton, determined to defend his property, grabbed a small hatchet that happened to be near him and swung it at the robber. The end result of this fracas was that Benton was severely beaten by the robber and another assailant and $6,000 - $7,000 worth of gold watches, diamond rings, and other jewelry were taken. Benton lived through the beating but it took a long time for him to recover.

That weekend and the next couple of days also saw robberies take place at other locations – an office, a shoe store, a cigar store, the home of August Sihefft, the home of John Martin, and the home of Seth and Cordelia Sheldon. The Sheldon’s lived on the southwest corner of Franklin Street and Duane Street (West 32nd Street today). The Cleveland Leader edition of May 12 said the Sheldon home “was entered by burglars, who carried off a lady’s gold watch and bracelet, worth $100. The thieves effected an entrance by breaking the blinds to the windows over the front porch, they having first ascended to the top of this.”

Later in the week the Leader reported, “Since the Benton robbery, unusual vigilance has been exercised by the police in apprehending suspicious characters with the hope of bringing the guilty parties to justice. This vigilance has been intensified by the commission of several burglaries on the West Side within the past few days, it being justly thought that a newly arrived gang of burglars and blacklegs had stationed themselves here to carry on their nefarious trade and every effort was made to discover their headquarters. On Tuesday Detective Laubscher received information which led him to look with suspicion upon a saloon at the south end of Pearl Street, known as the “Wacht am Rhein,” kept by John Rintenspacher. Six men, apparently strangers in the city, had taken lodgings there and their appearance and actions seemed to indicate that their employment might not be a legitimate one. The detective made his suspicions known to Captain Gaffett and Superintendant Schmitt and they coincided with him in the opinion that the gang must be watched and, if opportunity offered, captured on suspicion.”

Two plain clothes officers were stationed outside the saloon on Tuesday and Wednesday evenings. Their job was to observe the movements of these gang members which they found to consist of the men leaving the saloon in the early evening in groups of three and returning several hours later. The officers did not follow the men but simply observed their goings and comings. By Thursday the police felt the time had come to approach the suspected thieves.

John Michael Kick was a patrol officer for the Cleveland Police Department. Kick was of German descent, 35 years old, and had served in the Civil War as a color sergeant with a Missouri regiment. He had become an officer when the Police Department was formed in 1866. Kick lived on Myrtle Street with his wife Franziska and their four children, John, Eliza, William, and Mamie. In the book . . . In the Line of Duty, 1853 – 1999, published by the Cleveland Police Department, officer Kick is described “as a quiet, faithful, brave and fearless officer. His gentlemanly deportment and strict attention to duty earned him the respect of his fellow officers and all who knew him.”

On the evening of May 13, officers Kick and Floyd were stationed outside the saloon with orders to follow the suspects but to do so surreptitiously so as not to raise suspicions or create a brawl in public. Detective Laubscher also had placed a contingent of officers some distance south of the saloon, on Columbus Street, who were ready to surround and capture the alleged burglars. Laubscher went inside the saloon to observe the suspects expecting them to leave the premises soon. The problem was, that night the suspects broke their pattern of previous evenings by remaining inside the saloon and reveling in the music of a “couple of little Italian musicians.” Laubscher became concerned that his men might think that the plan of action had been abandoned so he left the saloon to advise his men as to what was happening.

Of course, as soon as Laubscher had left and gone a distance from the saloon the suspects emerged, walking rapidly, as a group, north along Pearl Street (West 25 Street). Kick and Floyd followed. When the suspects arrived at Franklin Street they turned and headed west toward Franklin Circle. Meanwhile Laubscher returned to the saloon only to find that the suspects and the officers had left but unsure where they had gone. Laubscher and his men headed north eventually arriving at Franklin Street but still unsure where the suspects and officers had gone since they were not in sight.

Kick and Floyd had met up with another officer, Patrolman Hildebrand, when they got to Franklin Circle. Together the three followed the suspects and when they came to the intersection of Franklin Street and Kentucky Street (West 38 Street) they confronted the suspects, thinking that Laubscher and his men were right behind them. The Cleveland Leader article goes on to say, “It was three to six, but the officers, not knowing the character of the enemy, thought nothing of danger. The gang had meanwhile separated; two were walking ahead with two more a short distance behind them and the other couple across the street. “We’ll take them all at once,” remarked Kick, “you take one couple Hildebrand, you another Floyd, and I’ll tackle the other two.” This line of tactics was adopted. The burglars were accosted and were asked what their names and occupations were. A wordy row ensued, the gang bestowing the strongest epithets upon the officers and telling them to mind their own business. As soon as they heard their questioners were policemen and bent on their arrest, and before, in the gathering darkness, their purpose could be discovered, they drew their revolvers and without more ado commenced to fire. The officers now saw that they were in for it, but determined to stand their ground, drew their weapons and a rapid firing on both sides ensued, the burglars shooting as they ran. In the first round a ball from the pistol of the ringleader struck Patrolman Kick as he stood on the middle of the street and he sank to the ground mortally wounded.

The other officers pursued the ruffians, firing at every step, and emptying the chambers of their revolvers before they gave up the chase. The pursuit was in vain, however, the scoundrels taking advantage of the darkness to make good their escape.”

The sound of gunfire in the neighborhood attracted many of the residents to come out of their homes. Some of them attended to officer Kick while others searched through the streets for the suspects. Kick was taken to the office of Dr. Robertson, just up the street at Franklin Circle. Dr. Robertson and Dr. Weed examined Kick and found the bullet had entered just below the heart then passed through the intestines and possibly the stomach. Kick was weak and apparently sinking fast. Kick’s wife and brother were called for and they stayed with him.

One of the gang members had run east on Franklin and turned south on Duane Street (West 32 street). He was seen by Patrolman Miller who, together with Patrolman Hildebrand, arrested the man at the intersection of Woodbine Street. The patrolmen took the fugitive to the Fourth Precinct Station where he said his name was James Moore, a stonecutter from Canada. “He, at first, pretended that he knew nothing of the gang of desperadoes, but a few vigorous measures extorted the confession that he was one of the gang and that he and the other five had come to this city from Chicago. At about eleven o’clock the prisoner was handcuffed and taken to the bedside of Officer Kick for identification. The wounded man was perfectly conscious and arousing himself looked keenly at the prisoner, saying decidedly, “He is one of the gang but not the man who shot me. He was a larger man. I would know the man who shot me if I saw him.”

In the hours that followed the police searched the saloon and the rooms where the gang was staying. They discovered three large trunks which contained merchandise stolen from a number of West Side homes including Seth Sheldon’s house. Three girls, two of whom were daughters of the saloon’s proprietor, were interviewed. They described the actions of the six gang members as men who worked nights when they did anything at all. They identified James Moore as James Highland, one the six men staying at the saloon. Police also found that officer Kick’s murderer was believed to be William Highland, brother of the man in custody.

The West Side was a relatively quiet and peaceful place and this incident generated feelings of indignation and fear that such an outrage could happen. “The scene on the West Side last night after the commission of the outrage was one that is not often witnessed in our peaceful city. Large crowds ran hither and thither, gathering at every point of interest and then separating in the common search for the outlaws. There was a very strong feeling in every heart that if ever Lynch Law is justifiable in a civilized community it would be justifiable now, and in the intense excitement of the time it is not unlikely that if the murderer had been caught a determined effort would have been made to hang him at the first lamp post.”

On Friday, May 14, officer Kick was taken to his home on Myrtle Street. At times he appeared to be recovering and at other times seemed to be failing. As he lay on his death bed Michael Kick dictated his Last Will and Testament. The document, witnessed by August Krause and Charles Cobelli, named Michael’s brother, George Kick, as executor of the will. To his mother, Anna Marie Kick, Michael left $200 for “her own proper use and benefit.” To his wife, Franziska Kick, he left everything else that he had, “Provided, however, that this shall only be of validity as long as she remains my widow, but if she marries again, then she shall only have a free disposal of one third – her dower – and only be allowed to use the other two thirds during the minority of our children; she shall properly support our children, and give to each, his or her share as soon as they become of age.”

Cleveland Leader, Monday May 17, 1875:

Officer Kick, of the Fourth Precinct, who received a mortal wound in the encounter with the band of Chicago burglars, on Thursday night, after lingering nearly forty-eight hours, died at twenty minutes to three o’clock on Saturday afternoon. . . The funeral will be held at his late residence on Myrtle Street, West Side, at two o’clock today, and will be attended in a body by members of the police force and the Phoenix Lodge No. 533, I.O.O.F. The members of both organizations will march from their respective headquarters to the residence at one o’clock. There will doubtless be a large attendance of citizens, who will take this method of showing their respect for the memory of one who has been a good citizen, a brave soldier, and a faithful officer.” He was laid to rest that day in Section M, Lot 74, at Monroe Street Cemetery.

Subsequent to Kick’s death the police continued to search for gang members. It was believed they were hiding in the country but despite exhaustive searches escaped, probably back to Chicago. The Board of Police Commissioners offered a reward of $500 for the arrest of Billy Highland and Henry Hill, who had been determined to have been two of the six gang members, and perhaps the murderers of officer Kick. James Moore, alias Highland, was incarcerated at the Central Police Station on two warrants taken out by Seth Sheldon and Mrs. John Martin, charging him with burglary.

On May 24 the Leader informed that James Colwell alias Moore alias Highland had been arrested in Chicago and brought back to Cleveland. The James Moore alias Highland arrested the night of the shooting was in fact William Highland. The real James Highland was an eighteen year old criminal said to be the leader of the gang. “The Chicago authorities say that this gang is one of the boldest and most desperate bands of burglars that haunt Chicago, and that any one of them would rather shoot than eat.” The murderer of John Michael Kick was never identified.

Officer Kick’s name is inscribed on the National Law Enforcement Officer’s Memorial Wall, Judiciary Square, Washington, D.C. on panel 52, west wall, line 4.

Though Michael had been laid to rest, for Franziska Kick the horror of 1875 was not yet over. During the summer two of her children became ill. On August 11 she buried her three-year-old son John who had died from pneumonia. On August 22 she buried her one-year-old daughter, Eliza, who died from Summer Complaint (Cholera Infantum). Both children were buried next to their father but without headstones.

Michael and Franziska’s son William died in 1937 at the age of 68 years and is buried at Monroe Street Cemetery. (William’s first wife, Elizabeth, is buried adjacent to Michael, John and Eliza.) Their daughter Mamie died in 1950 at the age of 79 years and is buried at Riverside Cemetery with her husband William Bruce.