August: 1839 – 1898

Wilhelmina: 1846 – 1914

Charles: July 9, 1882- March 2, 1927

On September 16, 1920, as the bells of Trinity Church in New York City’s Wall Street district were ringing noon, a dynamite-laden horse-drawn wagon exploded. The blast ripped into the lunchtime crowd at the corner of Wall and Broad Streets, killing 38 people and wounding hundreds more. This violent act is part of the story of decades of political violence in the U.S. The Haymarket bombing of 1886 had seemingly ushered in an era of dynamite attacks, mail bombs and assassination attempts on both politicians and capitalists, creating a widespread impression that dynamite and assassination were a vital part of American class relations. Yet, though this kind of terrorist violence was associated with the American revolutionary left, radicals in the U.S. disagreed about its legitimacy. Most embraced terrorism and assassination unapologetically, other left-wing notables like Socialist leader Eugene Debs and anarchist Emma Goldman tended to oppose such activity.

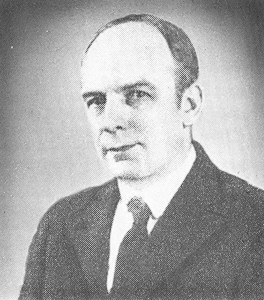

Some 16 months earlier than the Wall Street bombing an incident took place in Cleveland that shattered the calm of the first day of May 1919. The unfortunate, but predictable outcome of a simple parade exhibited a growing fear to which Clevelanders and, perhaps a majority of Americans, were reacting. The event came to be known as the “May Day Riots” and the simple parade had been organized by a man named Charles E. Ruthenberg.

Charles’s father, August Ruthenberg, had been a cigar maker in Germany and an activist in the German Social Democratic party but was not politically involved after he left Europe. August had four sons by his first marriage. His second marriage was to Wilhelmina Lau and they gave birth to three daughters before emigrating to the U.S. in 1882. Four months after their arrival their last child, Charles was born. At first, August Ruthenberg found work as a longshoreman on the ore docks, but later, he managed a saloon. Everyone in the Ruthenberg family worked except Charles. The child was his mother’s favorite, usually escaping chores and unpleasant tasks–much to the chagrin of his older siblings. Charles spent much of his time reading, and consequently did very well in school.

Ruthenberg’s earliest ambition was influenced by his mother’s desire that he become a Lutheran minister. In 1896, at the age of fourteen, he graduated from the Trinity Evangelical Lutheran School in Cleveland. His instructors remembered him as being shy and serious to the point of rarely laughing. Ruthenberg, however, did not pursue the clergy, for either lack of money or interest. Instead, he went to work in a picture frame factory, but did not care for a laborer’s life. He got a job in a bookstore, where his childhood interest in books and his new interest in salesmanship led him to a new career in business. He attended Berkey and Dyke’s Business College in the Standard Building at nights and graduated in 1898. Ruthenberg began his business career as a bookkeeper and salesman for the Cleveland district office of the Selmer Hess Publishing Company of New York. He achieved the position of assistant manager supervising about forty salesmen.

As a young man struggling for a living in the commercial world, Ruthenberg believed in the ideals of laissez-faire capitalism and Social Darwinism that were popular at the time. He continued to read widely. His favorite authors were Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Paine, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Henry David Thoreau, but their ideas of freedom, justice, and personal dignity were hard to reconcile with the materialistic values of the profit motive in business. Through these writings Ruthenberg became more aware of social problems and the need for political reforms. In 1901 he enthusiastically supported the candidacy of reformer Tom Johnson for mayor of Cleveland; his first political experience came from middle-class Progressivism.

By the age of twenty-three, Ruthenberg was a family man, having married Rosaline Nickel in 1904 and fathered his only child, a son named Daniel in 1905. He continued his intellectual interests by holding discussions in his home with friends and business associates. About this time Ruthenberg became interested in socialism through an associate at Selmer Hess, MacBain Walker who was at the time an admirer of the British Socialist Robert Blatchford. Ruthenberg found it difficult to refute Walker’s socialist arguments in numerous debates, so he read Karl Marx’s Das Kapital. He was so impressed with the book that he too began to advocate socialism and by 1912 was a militant party member.

As leader of the local Socialist party, Ruthenberg was an effective organizer and perennial political candidate. He ran for mayor 4 times (1911, 1915, 1917, 1919); for Ohio governor in 1912; for the U.S. Senate in 1914; and for the U.S. House of Representatives in 1916 and 1918, however none of these political aspiration came to fruition.

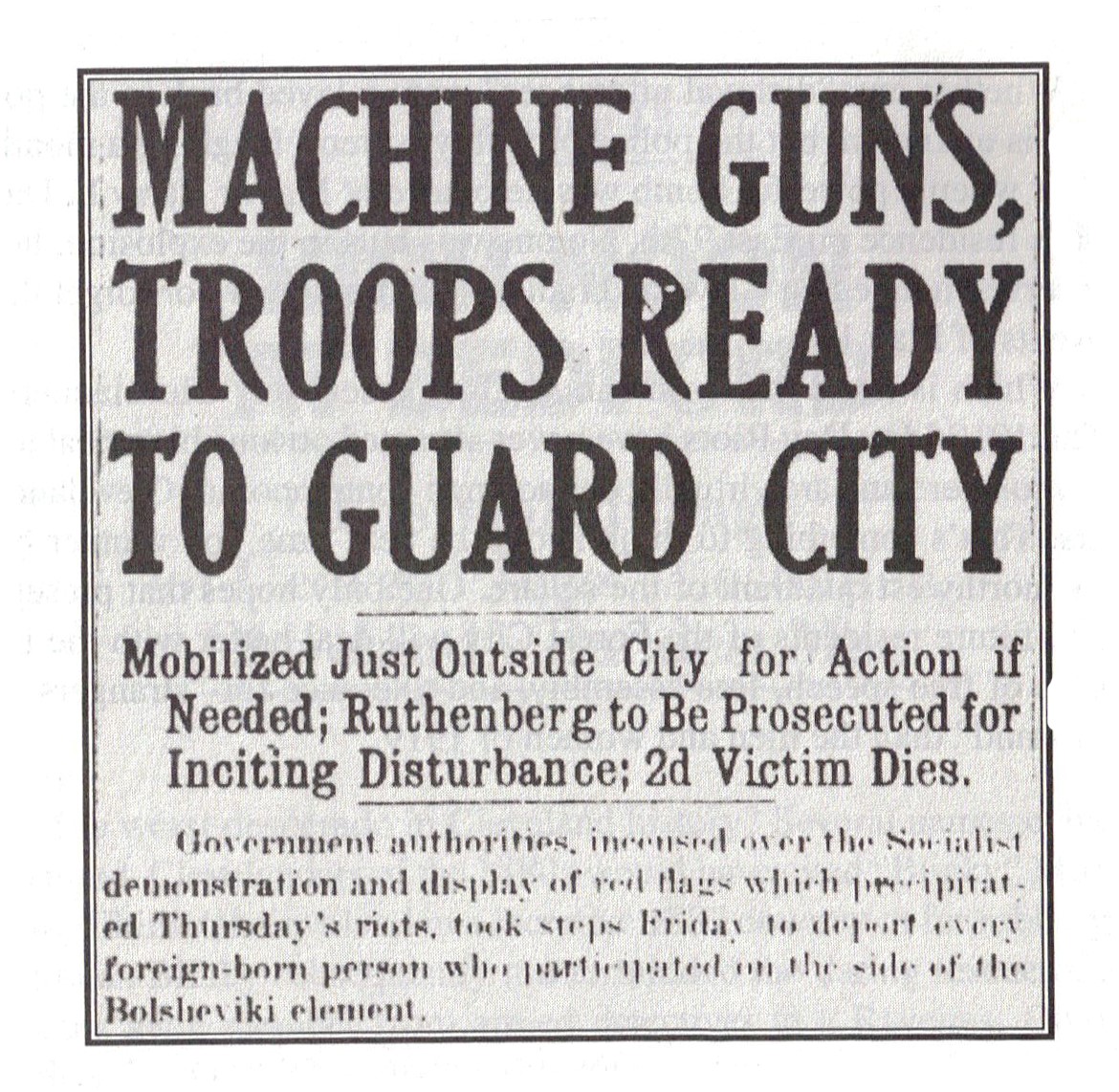

By 1917, Ruthenberg had given up his job to devote himself to political work, and had moved to the radical left of the party. After the Bolshevik Revolution, he switched to the Communist Party, becoming executive secretary of the Communist Party of America. Ruthenberg’s last major political action in Cleveland was leading the May Day Parade of 1919 which resulted in a riot and his arrest on a charge of assault with intent to kill. The decade from 1917 to 1927 was Ruthenberg’s most politically active era. He was arrested and jailed many times and it is said that during that decade he spent less than six months not incarcerated for some reason or other.

The Communist Party in Cleveland was a small, disciplined group of men and women involved in both political and labor activities who promoted the overthrow of American capitalism by revolutionary means in order to establish proletarian rule. The local Communist party was founded by Ohio and Cuyahoga County socialists belonging to the left-wing section of the national Socialist Party. The Cuyahoga County group left the Socialist party, upset that the National Executive Committee had nullified a party referendum favorable to the left wing at a New York section meeting on June 21, 1919. Led by Charles Ruthenberg, the left wing declared themselves the Socialist Party’s true national executive committee at a meeting held in Cleveland on July 26 and joined three other splinter groups to form the Communist Labor Party. The group affiliated with the Communist Party of America in May 1920.

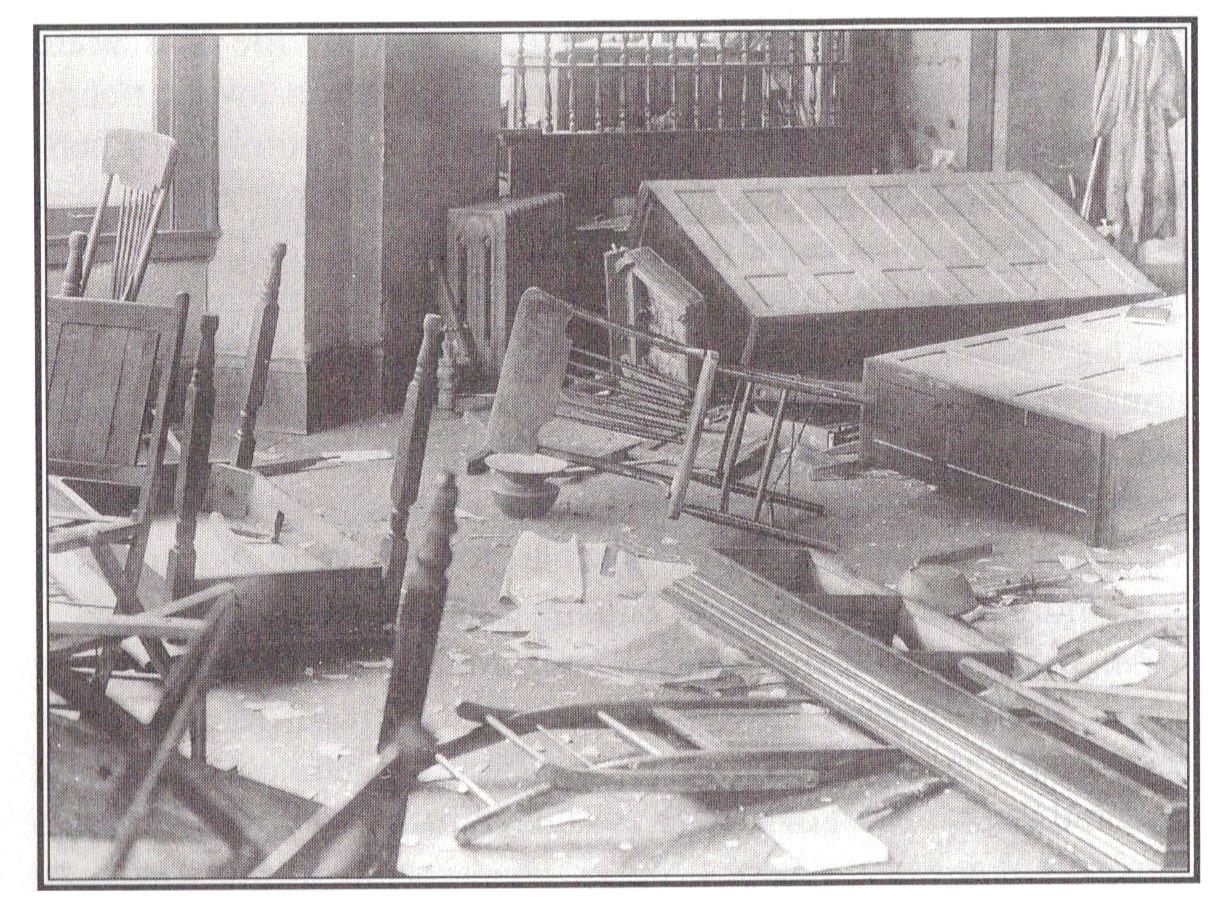

The May Day Riots involved Socialists, trade-union members, police, and military troops. The Socialists and trade unionists were participants in a May Day parade to protest the recent jailing of Socialist leader Eugene Debs and to promote the mayoral candidacy of its organizer, Charles Ruthenberg. Its thirty-two labor and Socialist groups were divided into four units, each with a red flag and an American flag at its head; many marchers also wore red clothing or red badges. While marching to Public Square one of the units was stopped on Superior Ave. by a group of Victory Loan Workers who asked that their red flags be lowered, and at that point the rioting began. Before the day ended, the disorder had spread to Public Square and to the Socialist party headquarters on Prospect Ave., which was ransacked by a mob of one hundred men. Two people were killed, forty injured, and one hundred sixteen arrested in the course of the violence, and mounted police, army trucks, and tanks were needed to restore order. Cleveland’s riots were the most violent of a series of similar disorders that took place throughout the U.S. Although it is uncertain who actually began the trouble, the actions of those involved were largely shaped by the anti-Bolshevik hysteria that permeated the country during the “Red Scare” of 1919. (For a more detailed account of the May Day Riots see the book They Died Crawling by John Stark Bellamy II.)

Charles Ruthenberg died suddenly on March 2, 1927, of a ruptured appendix. He was forty-four years old. His body was cremated in Chicago and sent by train to New York. His remains were sent from New York to Moscow, where his ashes were interred in the Kremlin Wall with full honors. John Reed and C. E. Ruthenberg are the only American Communists so honored by the Kremlin.

Ruthenberg’s death marked an important transition in the American Communist movement. During his leadership, the party had shifted from romantic clandestine revolutionary enthusiasm of 1917-1919 to organizational discipline and doctrinal subservience to Moscow. Ruthenberg never lost sight of the reasons why he had entered the movement, although policy changes by the Kremlin in the mid 1920’s made the hope for immediate revolutionary activity in the United States less likely. Whether Ruthenberg’s radicalism led to either personal happiness or self-fulfillment is not known. He lost years of freedom and sacrificed family life only to die at an early age with his dreams unrealized. His son has claimed that Ruthenberg had grown disenchanted with Communism by the mid-1920’s and was looking for a way out of the party, but there is no documentary evidence to support this view. He did not survive, in any event, to experience the profound disillusionment of his generation of American Communists that was caused by the brutal Five Year plans and purges by Stalin during the 1930’s.

Charles’ parents, August and Wilhelmina Ruthenberg, are buried at Monroe Street Cemetery though Wilhelmina’s name is not visible. Charles’ brother, William Ruthenberg, who died at the age of 72 in 1937 from erysipelas is also buried at Monroe.