Anson Smith 1795-1891

Amy Smith 1797-1877

Anson Smith was born in New London, Connecticut, and as a young man he started a very successful business as a woolen merchant. The great financial period of the 1830s found Anson’s business failing due to reversals he had suffered. He relocated to Ohio City in 1837 along with his wife and six children. There he quickly started a successful business shipping produce on the Great Lakes and the Ohio and Erie canals. Later he became a telegraph agent also.

Anson and Amy hired a governess to home-school their girls and the boys were sent to private schools and later Yale College.

Anson prospered and eventually was wealthy enough to join the well-to-do people on Euclid Street by having a home built on Millionaire’s Row, 1842 – 1846. Smith moved to Euclid Street in 1842 when he purchased a 5,000 square foot home formerly occupied by Judge Samuel Cowles for $7,000, a fabulous sum at the time. Homes on Euclid Street during the 1830s and 1840s resembled the native architectural conventions familiar to the families that had recently come from the northeast. Brick and stone rather, than wood, were used to capture the outlines of the Federal and Greek Revival styles. The Smith home would have been as appropriate in Athens, Greece, as on Euclid Street. The front of the house featured tall stone columns in the Doric Style, three bays wide, and supporting a decorated entablature. The main entrance was centered in the symmetrical façade.

Such a family certainly produced children and grandchildren that would, in their own right, be notable. The sons Robertson Smith (1839 – 1863), and Hamilton Lanphere Smith (1819 – 1903 ), and granddaughter Genevieve Estelle Jones (1847 -1879) each achieved notoriety in their own way.

In 1878 a close friend of Robertson Smith, Theodore Tracie, wrote a remembrance of him. Smith was born in 1839 and died at the age of 24 from a stroke.

“Lieut. Robertson Smith was a native of Cleveland, and served in the three months’ service in the same command with Shields and Wilson. He was a literary man from education and taste, and was a frequent contributor to the magazines and newspapers of that day. At the time of his entrance into the Battery he was connected with the Cleveland Leader in an editorial capacity.

He was a most genial and attractive gentleman, and very popular in Cleveland, where he was widely known, admired and respected. He was delicate in constitution and health, and had been most tenderly reared.

His entrance into army life was from patriotic convictions and a desire to serve his country, not from any taste or affinity for the profession of arms. Compelled to retire from the army after a few months’ service, on account of ill health, it would be difficult to anticipate what his success might have been as a military man.

In the annals of the Nineteenth Ohio Battery, I am thankful there are but few sad landmarks. The chiefest of these is indissolubly connected with one man. The inclemency of the season, and the delicacy of his constitution, soon told with marked effect upon Lieut. Robertson Smith, who was compelled to find in a private residence in town the comforts and luxuries which the camp did not afford. A low fever and general debility were followed by a severe attack of typhoid fever, which prostrated him and confined him entirely to his apartment. He was visited almost every day by the officers and men, and though weak and unnerved from the attacks of the disease, he always had a kind and pleasant word for everyone. He was a universal favorite in the command, and few men in military life were so fortunate as to win such love and hearty regard from his comrades as Robertson Smith.

He was a man of somewhat eccentric character, and full of quaint humor and harmless cynicism. He affected to regard everything in life in anything but a serious aspect. To a well-stored mind and a cultivated taste were added rare gifts and culture, which in time would have made him conspicuous in literary and aesthetic circles. Like all of nature’s true gentlemen, he had the happy faculty of adapting himself to circumstances, and in making those around him feel their troubles and trials less.

His recovery became so doubtful that his physicians decided it necessary that he should resign and return home. Accordingly, his resignation was forwarded and accepted, and a time set for his return to Cleveland. The ambulance was sent to town, at his request, and he was brought to camp to see his comrades for the last time.

It is but fitting that this memorial should include the sad event which followed some months later. We had passed through many exciting scenes, of which Lieut. Smith had been kept advised; the summer was gone and early September was upon us, when the startling announcement was made that Robertson Smith was dead:

As I recall that day and the feelings that announcement aroused, it seems but yesterday that I had been bereaved, and my heart saddens even after these many years, as I write the word dead after my friend’s name.

I was lying in the hospital tent recovering from a fever when I received a letter in his familiar handwriting, and proceeding to open it with trembling eagerness, my eye fell upon some penciled words on the back of the envelope. As I read them, my heart stood still and my eyes were blinded. It seemed impossible that I could have read aright, and yet the words were there and would not out: “Robertson died today at half past five o’clock. Please inform his friends in the Battery.”

The post-mark bore a date almost a month old. The hand that had written kindly words to me, and the heart that had prompted them, had been stilled in death weeks before the missive had reached me. The end had come.

Accompanying his letter was one from his sister, thoughtfully giving me the details of my friend’s last hours. I opened a Cleveland newspaper and read there the printed tale of his death, which I here reproduce: “It becomes our painful duty to chronicle the sudden demise of Robertson Smith of this city, late second lieutenant in Shield’s Battery, which event occurred at the residence of his father on Euclid street, about six o’clock last evening. Up to within a very short time before his death, Mr. Smith was apparently in the enjoyment of his usual health—which, however, has been delicate for several months—and in fact he had seemed during the day to have been in even better spirits than usual. Between four and five o’clock he was seized with violent convulsions while ascending the stairs to his room, and it was there that the family, attracted by his groans, found him. Notwithstanding that every effort was made to relieve the sufferer, he sank rapidly until death relieved him from his sufferings. The deceased was entirely unconscious from the moment of the attack until his death. The latter was undoubtedly caused by a disease of the heart with which he had been afflicted for some time.”

Hamilton Lanphere Smith was an Americanscientist, photographer, and astronomer. He was born in New London, Connecticut and graduated from Yale in 1839,[1] where he constructed the largest telescope in the country at the time in 1838.

In 1848 Smith wrote “The World”, one of the first science textbooks written in America. Smith is best known for patenting the tintype photographic process, which popularized photography in America. He patented the great American tintype on February 19, 1856.[1]

Between 1853 and 1868 he was Professor of Natural Philosophy and Astronomy at Kenyon College, Gambier, Ohio, and later taught at Hobart College in New York. He also created a system for describing microscopic algae that is still in use today.

Upon his retirement from Hobart, Smith returned to Yonkers, New York, where he was cared for by his granddaughters, and their mother, Mrs. Buttles Smith. Smith died on August 1, 1903, at the age of 85 years. Smith and his wife are buried in Geneva.

A tintype, also known as a melainotype or ferrotype, is a photograph made by creating a direct positive on a thin sheet of metal coated with a dark lacquer or enamel and used as the support for the photographic emulsion. Tintypes enjoyed their widest use during the 1860s and 1870s, but lesser use of the medium persisted into the early 20th century and it has been revived as a novelty in the 21st.

Tintype portraits were at first usually made in a formal photographic studio, like daguerreotypes and other early types of photographs, but later they were most commonly made by photographers working in booths or the open air at fairs and carnivals, as well as by itinerant sidewalk photographers. Because the lacquered iron support (there is no actual tin used) was resilient and did not need drying, a tintype could be developed and fixed and handed to the customer only a few minutes after the picture had been taken.

The tintype photograph saw more uses and captured a wider variety of settings and subjects than any other photographic type. It was introduced while the daguerreotype was still popular, though its primary competition would have been the ambrotype.

The tintype saw the Civil War come and go, documenting the individual soldier and horrific battle scenes. It captured scenes from the Wild West, as it was easy to produce by itinerant photographers working out of covered wagons.

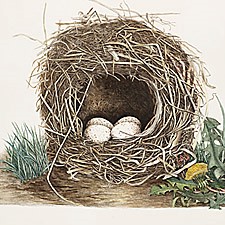

Genevieve Estelle Jones was born in her grandfather’s home in Cleveland, Ohio, and named after one of her mother’s sisters. She was bright inquisitive child who loved to be out-of-doors. When she was only a toddler, her father commissioned a set of miniature gardening tools from the blacksmith so that she could work outside along with the gardener. She moved to Circleville with her family at the age of six. Soon afterward she began a lifelong practice of riding with her father in his buggy as he visited his patients. She was home-schooled by her mother, who also taught her watercolor painting, until she was of high school age. She attended Everts High School and graduated in 1865. After that event, her education was continued at home where she was tutored in Greek, French, Latin and German and studied the piano until her teacher refuse to continue taking money for lessons because she had become a better musician than she was.

Genevieve died at the age of 32 years but during her lifetime her deep interest in nature and out-of-doors combined with her drawing and painting ability led her to create a substantial number of paintings of wildlife and, in particular, bird’s nests. Her works were only known to herself and her family but after her untimely death the family created a memorial to her.

Illustrations of the Nests and Eggs of Birds of Ohio was published in the small town of Circleville, Ohio, over a period of eight years (from 1879 to 1886) through the dedicated efforts of the family and friends. Despite being produced not just by amateurs but largely by women, far from the publishing houses and the intellectual centers of 19th-Century America, the book was hailed as an extraordinary achievement from the moment it’s first few pages were published. Elliot Coues, one of the foremost American ornithologists of the period, praised the book as it’s parts came off the press and were distributed. In the pages of The Auk, the journal of the American Ornithologists’ Union, and its predecessor, The Bulletin of the Nuttall Ornithological Club, he described it as a “magnificent work” of “great artistic excellence and fidelity to nature”. The plates, he wrote, “compare favorably with the best that have ever appeared.” He placed it “among the most original and most notable treatises on ornithology which have appeared in this country.”

Published by subscription, a common means of financing large expensive books in those days, no more than 100 copies were made. Fewer than that survive today, so it’s very scarce, and few people have ever seen it.

Anson and Amy Smith decided that in spite of their substantial wealth they would be buried at the Monroe Street Cemetery and their monument is a very modest marble one which has been damaged by the ravages of the industrial atmosphere that was prevalent in Cleveland for so many decades. Perhaps the reason they selected Monroe Street Cemetery is that their son, Robertson Smith, is buried in Section E, Lot 1, the same location as Anson and Amy.