Ella Grant Wilson 1854 - 1939

The death of Ella Grant Wilson on December 16, 1939, ended the career of a business woman who became widely known to fellow Clevelanders for over half a century through her work as a florist and her articles on gardening and early Cleveland history in the Plain Dealer. She died at the age of 85 after a protracted eight-week illness in a Cleveland nursing home. She was stricken a few weeks after she observed her birthday in September. Her body was taken to the Young-Baker funeral home where services were conducted by Rev. Walter H. Stark of Pilgrim Congregational Church. Ella Wilson had arranged many weddings and funerals at that church. Mrs. Wilson, friend to many of the distinguished men and women who built the mansions that made Euclid Avenue famous at one time as the “most beautiful street in the world, was known to thousands of Clevelanders through her writings on horticulture and her interest in the early history of the city.

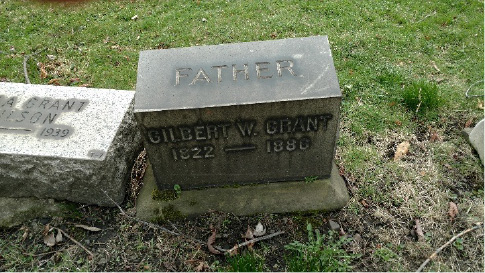

She was born in Jersey City, New Jersey, in 1854, the daughter of Gilbert Grant and Susan Lawton Grant. She had a sister named Ida and a brother named Gilbert Leonard Grant. In 1860 the family moved to Cleveland and Mrs. Wilson made her home there for the rest of her life. Her first residence was at Prospect Avenue and Perry Street (now E. 22nd Street). Ella was eight years old when she sold her first flowers. She didn’t exactly sell them but a man came past the yard where she was tending her flower garden and gave her two circus tickets in exchange for a bouquet. Little did she know at the time what lay ahead for her.

One of Mrs. Wilson’s earliest recollections, and one which she described in several newspaper articles as well as her first book “Famous Old Euclid Avenue,” was her trip to Public Square in 1865 to view the body of Abraham Lincoln as it lay in state. She was unable to see over the side of the casket, even by standing on tip toe, and a man standing nearby stepped forward, lifted her up and said, “Little girl, there lies a great and good man. Never forget him.” The man who lifted her up was Salmon P. Chase, chief justice of the United States.

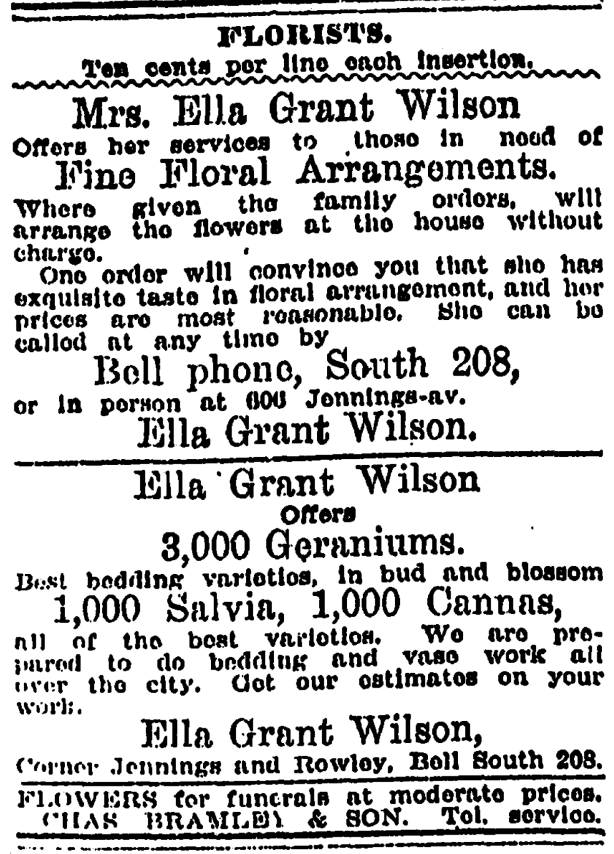

When Mrs. Wilson was fifteen years old her father who, at that time, was one of Cleveland’s leading oil men, suffered financial reverses and she decided she must do something to aid her family. She had always loved flowers and finally found a position with a florist, a position that lasted but four months, when she was unceremoniously dismissed with the prediction: “You probably will never amount to much as a florist.” With ten dollars she had saved and one hundred dollars she had borrowed, Mrs. Wilson set herself up in a business that was later to give her entrée into the homes of Cleveland’s wealthiest and most prominent citizens. The following memoir is taken from Famous Old Euclid Avenue of Cleveland written by Ella and published ca. 1930

The Garfield Funeral

The Garfield Funeral stands out as one of the big events of my life, as I played an important part in it. When the news flashed across the country from Elberon, Sept. 19, 1881, that President Garfield had died, all Cleveland mourned with every other city, town and hamlet in the United States. As the Associated Press voiced it:

The Silver Cord is loosed, The Golden Bowl is broken; The Spirit has returned to God Who gave it.

All the business houses-expressed their sorrow in drapings of black. Every house had some expression of its sorrow. Garfield was well loved in Cleveland and throughout northern Ohio. The catafalque was a work of art. It was the conception of Coburn and Barnum (ed., Architects). The funeral was in charge of Hogan & Harris, funeral directors, who designed a funeral car covered with black broadcloth, with great bunches of black ostrich plumes, which emphasized the corners of the canopy, and left the casket in full view. It was drawn by twelve spirited black horses, decorated with nodding plumes and with broadcloth covers trimmed in silver, each horse led by a groom.

Members of the Cleveland Grays marched beside the funeral car. Cleveland never had' a greater outpouring of prominent men than came to do honor to Garfield. The committee of arrangements included not only R.R. Herrick, mayor, but practically every prominent man in Cleveland at the time: Amasa Stone, J. M. Hoyt, William Edwards, William Bingham, George W. Gardner, T. P. Handy, Mark Hanna, Edwin Cowles, Dr. Kitchen, Amos Townsend, Col. A. T. Brinsmade, Col. W. H. Harris, John Farley, Capt. John N. Frazee, Wm. H. Eckman, Lee McBride, W. H. McCurdy, C. P. Leland, W. H. Doan, H. B. Payne, Joseph Perkins, J. H. Wade, Selah Chamberlain, P. T. Babcock, E. R. Perkins, S. T. Everett, Gen. James Barnett, E. P. Wright, H. S. Whittlesey, Dan P Eells, Geo. P. Ely, Silas Merchant, William W. Armstrong, John Tod, Dr. W. S. Streator, Capt. Louis Smithnight, Edgar Decker, G. N. Andrews, D. McClaskey, Gen. J. H. Devereaux, Gen. M. D. Leggett, Judge Rufus P. Ranney, J. H. Rhodes and Dr. J. P. Robinson. These show the caliber of Cleveland's business men of 1881.

But to go back a little. When the news came of Garfield's death, I went at once to the city hall. I found N. A. Gilbert in charge of all floral effects. He was chairman of the decorating committee. I was acquainted with both he and his wife. This committee was holding a meeting at the time, and I was called in and asked for suggestions. I gave my ideas and they were quickly approved. I was given, the order and placed in charge. For two days and two nights I only slept about four hours out of the forty-eight. I was then given charge of the four arches over Superior and Ontario streets. The crowds bothered me badly and I spoke to Mr. Gilbert about it, and, through Mayor Herrick, the Grays were ordered out to protect the workers. The first thing they did was to order me out of the Square. I protested that I was in charge of the work, but the officer in command said, "Sorry, lady, my orders are to clear the Square of everyone who cannot show a badge."

I had been too busy to get to the city hall for a badge and I had a hundred and forty men to keep at work. I spied Mr. Gardner passing with some men. He was at that time president of the city council. I said, "Mr. Gardner, they have put me out of the Square and the men are looking to me for orders. I have no badge. The Grays were sent down here to protect me and my men, and instead they've put me out. What shall I do?"

He took off his black leather badge, embossed in gold leaf and inscribed, "Garfield Obsequies, Sept. 26, 1881," and across the center, "City Council," and handed it to me. Though another badge was prepared for me as "Superintendent," I wore the city council badge throughout the services. That is the nearest I ever came to being a member of the city council.

The last six hours I was on duty, I existed on ice water. The men indulged in something stronger, and it wasn't bootleg, either. One of my conceptions for the occasion was called the "Garfield Ladder." This was used on the arch facing east on Superior street. It was 18 feet high. At the base was a canal boat, the "Evening Star," on which the president worked when he was a boy, and then there were successive rungs to indicate his progress in life. At Chester, Ohio, he first went to school. At Hiram and Williams he attended college. Then followed his public career, colonel, general, congress, senate, president, martyr. Surmounting all was a crown and cross. Near the top was a Maltese Cross typifying his Masonic affiliations. At the base of the cross was the United States shield, draped in black with the dove of peace holding in its bill a white ribbon carrying this inscription, "In Memoriam."

The press all over the country carried descriptions of this piece of work and gave Miss E. L. Grant credit for it. It was at this time, that I woke up to the value of publicity. Three days after the funeral a mail truck stopped at my south side place of business and the man asked me, "Where do you want your mail?"

I looked a little surprised and said, "Why, give it to me here," indicating the counter in front of me. He took up a mail sack and commenced to empty it out on the counter. The letters not only filled up the top of the counter but fell to the floor. I scratched my head and looked in amazement.

Every letter asked for a souvenir flower from the Garfield funeral. The next day, a full bag was received. These letters I emptied on a bed sheet I placed on the floor. I then tied the four corners of the sheet together and took them over to the city hall to the Garfield committee.

The committee sent a letter to all those who had written in, offering to mail a souvenir flower to all who sent in 25 or 50 cents. Many did send in their money and it was turned over to the memorial committee, and applied toward the cost of erecting the monument standing in Lake View Cemetery today.

This was the beginning of my large acquaintance locally. Mr. Gardner recommended me to the secretary of the Chamber of Commerce, and for 18 years I had charge of all floral orders emanating from the Chamber, and for the same period I had charge of all work and the care of plants in the Hollenden Hotel. These connections made me acquainted with many of our leading citizens; with those men who were developing Cleveland.

Florally, I helped at their banquets, dinners, luncheons, and arranged the last tributes of affection around them. I must have given satisfaction or I would not have been retained so many years, for competition was as keen in those days as it is in these.

Euclid Avenue

Euclid Avenue was a village road when Mrs. Wilson first knew it but in her lifetime were erected the mansions of Amasa Stone, Samuel Mather, Charles F. Brush, S.T. Everett, Samuel Andrews, Edwin Hale, Bishop Leonard, Judge Ranney, the Chisholms, the Wades, the Perkinses, the Hoyts, and Judge Stevenson Burke. Not only did she know the houses, but what went on in them – the weddings, receptions, balls and musicales. On April 22, 1909, a cyclone swept away her greenhouses at W. 14th Street and Rowley Avenue S.W. standing by helplessly she saw the storm hurl 1,000-pound potted plants across the greenhouse paths and saw it bury her eldest son, Carl, under the debris. The chimney of the heating plant, which was fifty feet tall, fell and the falling bricks shattered all the glass in the greenhouses and tore down the boiler shed in the rear of the property. Carl, who was in the boiler shed, was saved by the iron steam pipes overhead that stopped the fall of the wreckage. He was unharmed and taken out of the wreckage by firemen, but the flowers that she had tended so carefully were ruined and she never went into the growing business again.

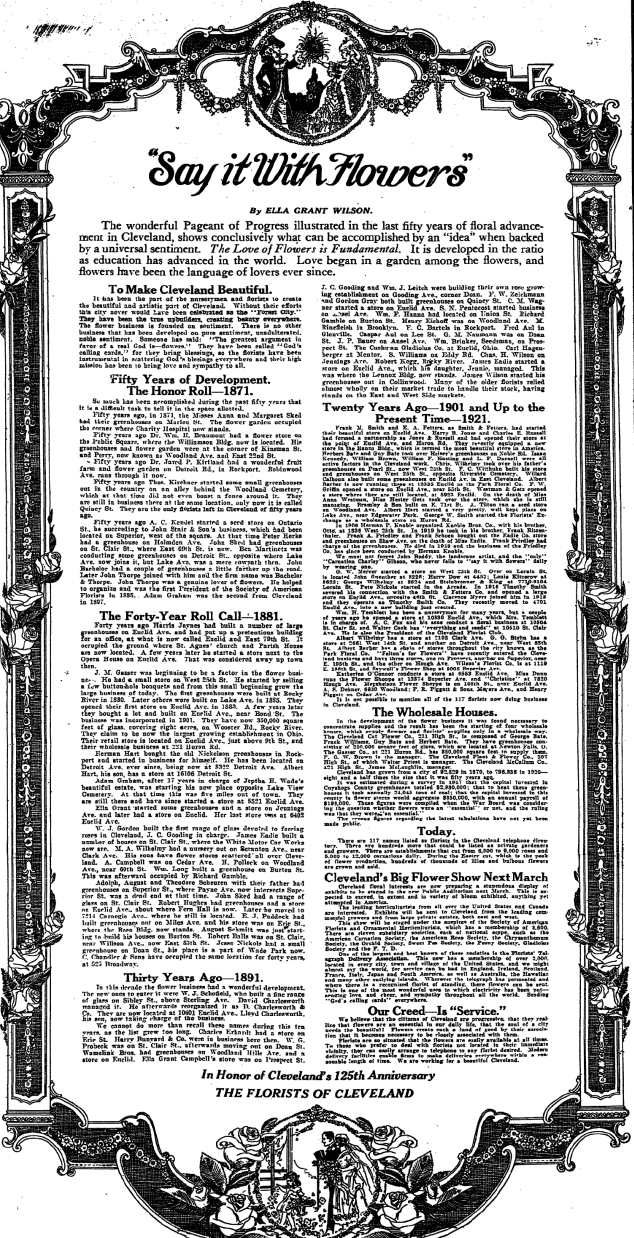

In 1918 she began writing articles on horticulture for the Plain Dealer, and in 1929 began a series of articles in the Sunday Plain Dealer magazine section on the early history of Cleveland and Euclid Avenue. The stories were later collected and printed in augmented form in her book “Famous Old Euclid Avenue of Cleveland: At One Time Called the Most Beautiful Street in the World.” In 1937 she arranged and released the second volume, which tells the history of houses along the Avenue from what is now E. 30th Street to E. 79th Street.

When Mrs. Wilson retired from her job at the Plain Dealer her daughter, Helen Grant Wilson, became the garden editor. Having been born in 1892 in the house on Jennings Avenue (W. 14 Street) next to the greenhouses, she lived among flowers and plants and regarded them as her friends. Her father was Charles H. Wilson who was an orchid grower of international repute. Ella and Charles had been married on July 29, 1891, and operated a florist business together. They brought four children into this world – Helen, Carl, Fern and Ernst. The marriage to Charles was a second marriage for Ella. She had married James Campbell and they gave birth to a daughter named Pansy. James, however, died soon after the marriage.

The marriage to Charles, however, did not go smoothly. In a Plain Dealer article from October 14, 1906, “Mrs. Ella Wilson says Charles H. Wilson has been in the habit of spending too much money for enjoyment that she does not participate in and at her expense. It is alleged by Mrs. Wilson that her husband stayed out late at night, then came home and abused her. . . .This petition asks for an order restraining her husband from interfering with household effects or coming near his wife.” On November 9, 1907, Mrs. Wilson was granted a divorce by Judge Phillips and was given custody of her four minor children. Charles died March 13, 1913 and is buried in Calvary Cemetery.

The Columbian Exhibition in Chicago occurred in 1893. In November of 1892 a Woman’s Columbian Association of Northern Ohio was organized in Cleveland. Its object was to promote the interests of Cleveland women at the world’s fair. The organization decided to recommend Ella Grant Wilson to the authorities at Chicago as a proper person to superintend the decoration of the grounds about the women’s building. In 1906, one hundred years after the death of Moses Cleaveland, the founding father of the city of Cleveland, a monument was to be erected in the Canterbury Connecticut cemetery where Moses and his wife are buried. A magnificent wreath was arranged by Mrs. Wilson to be laid on the founders grave. A cluster of flowers was also prepared to be placed on Mrs. Cleaveland’s grave.

Subsequent to the disastrous fire at the Collinwood School in 1908 floral offerings that marked the funeral of the unidentified dead crystallized the sympathy of a nation. All of Clevelands’ florists contributed their choicest blossoms. Schoolchildren from schools throughout Cleveland carried bouquets of fresh cut flowers for both the dead and the living. These bouquets were arranged by Mrs. Wilson.

In August 1921 Mrs. Wilson was one of thirty-five Clevelanders who attended a reception of visiting florists in Washington, D.C., given by President and Mrs. Warren G. Harding. In preparation for the March 1922 fifth national flower show, which was to be held in the recently completed Cleveland Public Auditorium, Mrs. Wilson extended an invitation to the chief executive to attend and he expressed a willingness to do so. Mrs. Wilson, who was the secretary of the Grant Family Association of Ohio and a third cousin to former President Grant, had traveled to Cincinnati in April of 1922 intending to board the steamer Island Queen before it started its voyage to Point Pleasant where Mrs. Wilson was to present a bouquet of flowers to President Harding. Unfortunately while running to catch the boat she tripped, fell and was injured sufficiently that she could not go on board.

In September 1933, when Mrs. Wilson was 79 years old, she had been in poor health for about a year but insisted on attending the Fall Vegetable and Flower Show at the old Higbee Co. store at E. 13th Street and Euclid Avenue. She was looking at one of the flower exhibits when she suddenly collapsed. She was unconscious for several hours but her physicians gave her an even chance for recovery. Attendants at the hospital felt that the weather, which had been cold and damp, was probably responsible for the sudden attack.

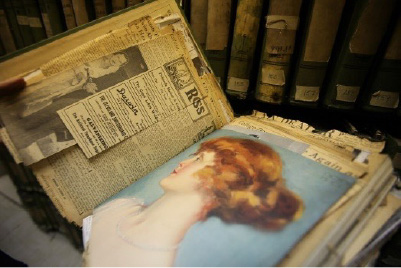

Scrapbooks were Mrs. Wilson’s favorite hobby. She built up a collection of 362 volumes of clippings collected over a period of 50 years on Cleveland, prominent Clevelanders and horticultural subjects. In 1934 Mrs. Wilson scattered her large library of scrapbooks, giving them to organizations and members of her family. Western Reserve Historical Society received 200 volumes dealing with biographical and historical matter. One hundred and fifty horticultural volumes were divided equally between her son Carl and her daughter Helen. Twenty volumes were sent to the Florist’s Telegraph Delivery Association to be kept in their home in Detroit. The remainder of the collection, dealing with personal affairs, was kept as an heirloom. It was at this point in her life, age 80, that she gave up her home and went to live with her children.

At the time of her death Mrs. Wilson was a member of the Cleveland Writers Club and the Mothers Club of Pilgrim Congregational Church, a life member of the Society of American Florists and an honorary member of the Lakewood Garden Club and the Florists Club of Cleveland.

Ella Grant Wilson succumbed to cervical cancer on December 16, 1939, and was buried next to her father at Monroe Street Cemetery, Section T, Lot 7. Cemetery records do not indicate if Ella’s mother is also buried there. Her son Ernest (or Ernst) died at the age of 53 in 1950 in Jackson, Florida. He was cremated and his ashes were sent to Cleveland where they were scattered on top of the family plot.